Two themes have emerged recently in my psychotherapy practice, and in the mirror: relief, and exhaustion. Some peace in the public discourse, or at least a pause in the ominous discord, has had the effect of a lightening, an unburdening. A hint of release from a contracted sense of tension around the specifics of violence and a broader sense of civil fracture has been palpable like a big, deep breath, exhaled.

No sensible person would mistake this for being out of the metaphoric woods. A virus menaces and mutates, economic woes follow, and lots of us don’t get along. But, yes, there is some relief, some good change.

But even good change, even a downshift into relief, can pose some challenges to look for and even overcome.

Consider for a moment the notion that every change represents a loss, the "death" in a metaphoric sense, of a prior state of things. This is true of big, painful losses, like the death of a loved one, and small ones, like finding the cookie jar is empty. It's also true in changes we associate with benefit or relief: a refund check, a job promotion, a resolving migraine, or the breaking out of some civility.

In changes of all sorts, the world outside of one’s mind has shifted—at odds, momentarily, with our inner, now obsolete understanding of that changed world. The inside of the head does not match the outside. How we make that adjustment, so “inside = outside,” that process is a culturally familiar one: it's grieving, that sequence famously elaborated upon by the late Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and others.

You may know the steps: shock/denial, anger, “bargaining,” depression, and acceptance. A quick explanation: our initial anxious/threat reaction leads to grievous judgment, leads to rationalizing “woulda/coulda/shoulda’s,” leads to truly landing in the disappointment of a loss or change, leads to an accepting of a new steady state. Inside proceeds to match outside.

So, what then of relief? How do we process “good” change? I’d propose that we still must move from "in ≠ out" to "in = out," navigating some pitfalls along the way.

- Initial threat often remains; the initial apprehension of the “new” still can generate energy, and even a sense of threat, regardless of a kiss or a shove. Our brainstems run roughshod over this first phase.

- Step two is about judgment. We can move past threat to “how do I feel about it?” Here’s where grievous feeling gets swapped out for something more peak-positive—joy, or relief if the change represents an ending of a state of suffering, tension, or uncertainty.

- The “bargaining” step still happens, but often around a kind of testing regimen: is this too good to be true? Is it really different? We run our scenarios.

- The thud of disappointment also gets a makeover. It’s a settling into the beneficial change and its associations: gratitude, a sense of relaxing and energy shifting.

- The bookend “OK” seems anodyne here—why would anyone not accept relief, some good change? But it can nevertheless represent a challenge for many. The receding tension of the recent stretch of time could open into a burst of energy, but I'm finding that exhaustion is just as or more common. That's not illness, but a weary exhaling from the longest of held breaths.

One other twist: What happens when one of those steps is an individual obstacle, trigger, or hard-to-hold state? Especially for those of us with deep experience in disappointment or even trauma, buying into acceptance of a new steady state can feel like a fool’s game. This is sometimes an especially complex spot for individuals who won’t quite allow for joyful acceptance to break out, lest it turns into a humiliating trick or a too-brief respite from the “usual.”

Grief, and relief, are complex processes that generate not just one state of experience but a cascade of them. While that cascade can hurt, it's actually normal, not illness. But it can be exhausting.

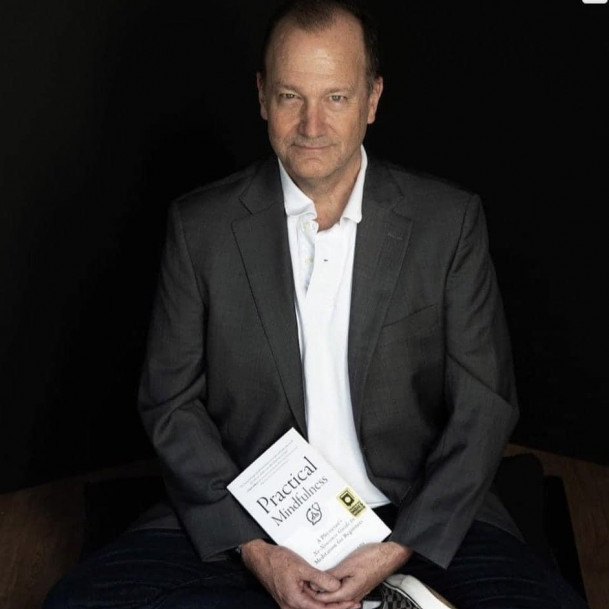

Our felt states of any of the steps noted above in metabolizing change, can become more familiar and identifiable as a "pattern set" in body, heart, head, and clarity of awareness itself. Mindful practices in knowing well our inner states and tendencies makes these processes more transparent to us, knowable, even anticipated. It can get more complicated from there: what happens when one of those steps is an individual obstacle or a trigger?)—but that's another post.

What else do I advise? Patience, and some compassion for ourselves in this unusual time.