You can’t open a newspaper or browse a health website these days without seeing the latest glowing testimonial to the benefits of meditation training. Of course, in many places, you can't "open a newspaper" anymore, period. But you get the idea.

Yet only a small subset of health care professionals actually practice meditation, and fewer still incorporate awareness training into their "toolkit" in treating their patients. It’s not as if there has been an absence of attention to meditation in healthcare. The works of Jon Kabat-Zinn, Mark Epstein, Marsha Linehan, and others have reinforced meditation’s benefit on most chronic medical and psychological suffering.

Nevertheless, many health care professionals have not jumped in the pool. The reasons for this are not complex but are particular to our clique.

- We're crazy busy. Learning to meditate is its own process that takes some time and patience. Understanding in practice enough to conveys its basics to our patients, even some more. Squeezing even basic meditation skills training (ours, then theirs) into our already over-subscribed professional lives can be daunting, even as it does not require its own EHR workflow chart reminiscent of a Jackson Pollock work.

- We're nerdy. (Yeah, we are.) Some of us can mistrust the validity of a practice that entrains observation of a subjective, poorly measurable interior experience. No serum nirvana level exists, at least with an agreed-upon reference range.

- We're control freaks. (Well, not me, but, ok, yeah.) Others are not excited about working with a tactic that produces an uncertain outcome, at least in the near-term. Western-trained minds may misunderstand it as uncomfortably associated with unfamiliar, Eastern spirituality.

Regardless of our possible reasons for stiff-arming it, meditation training is a truly valuable, thoroughly secular tool for medical and mental healthcare professionals to incorporate into our patient practices—and our own personal self-care routines. The benefits? How about three more bullet points?

- There's a therapeutic benefit. Initial training in concentration practice—using the breath, body sensations, or an external visualized object—has its rewards in entraining calm and adaptation. Treaters and patients need not go any further to reap the benefit of basic meditation’s calming effect.

- The cultivation of self-awareness is a true diagnostic benefit for treater and patient alike in identifying one's own individual patterns of reactivity. These somatic, emotional, thought, and attentional effects often co-occur in the midst of relating "there-and-then" events, and even more powerfully in the real-time reactions in a medical or psychotherapy event.

- Lastly, there's an attitudinal benefit of regularly bringing notions of compassion, equanimity, and gratitude to explicit attention via meditation practices. Grooving in a compassionate vibe as a healer can be a powerful modeling example for patients on our best days, and kind of attitudinal a life raft for us on our most distracting, stressful ones.

The instructions in beginning meditation are not complicated; they can be taught to patients briefly and easily as we do with information on sleep hygiene, mood diaries, and other helpful clinical routines. Nevertheless, in guiding patients through a practice about an interior, subjective state, nothing can replace our direct engagement in basic meditation before teaching it to patients, as well as in modeling its benefits.

The hackneyed but valid bromide we may remember from medical training, “see one, do one, teach one,” is applicable here. Another, “physician, heal thyself” may also apply.

References

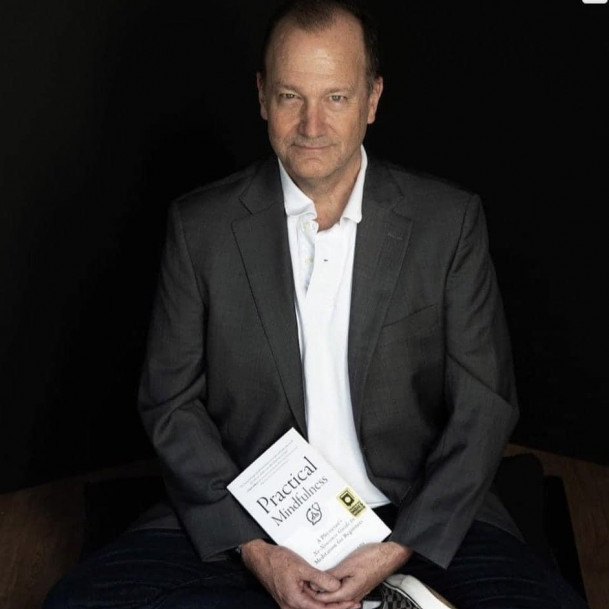

Sazima G. Practical Mindfulness: A Physician's No-Nonsense Guide to meditation for Beginners. Mango Press; 2021.