One would think that persuading our patients to take up a practice that promises benefits in calm, reduction in physical and emotional suffering, and improved clarity of thinking would not require the skill set of a used car dealer.

Alas, it can be that way with meditation. So, why is that?

- For patients, there can be a lack of understanding about what the practice is and does.

- Mistrust about mindfulness being a mystical or religious experience being cloaked in secular garb can play a role.

- There's also the psychological irony of an "ask" that encourages collaboration of caregiver and patient. It tips the power balance away from a regressive, "parent/child" model of treatment, a beneficial tipping in theory. But some patients (and caregivers) may remain married to a one-way model of health care treatment.

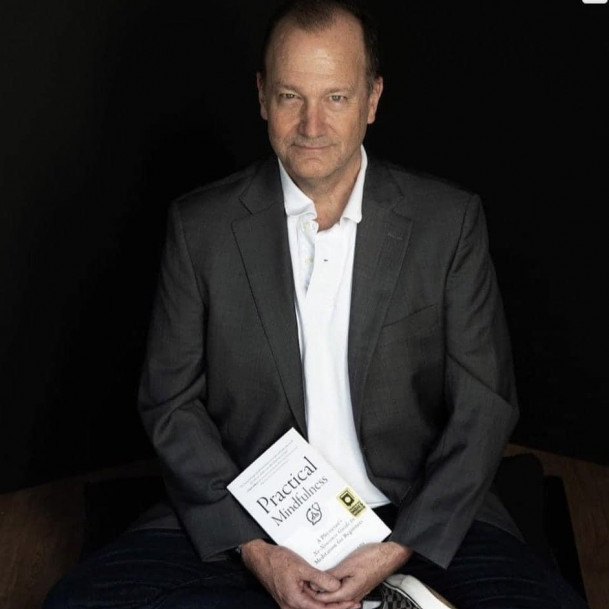

Once we make the "sale," the instructions in beginning meditation are not complicated for us to learn, then to convey to others. Ultimately they can be initially taught briefly and easily, as we do with information on sleep hygiene, monitoring of mood changes, and other helpful clinical stuff. (Brief book plug: Practical Mindfulness features an appendix for professionals specifically on teaching introductory breath meditation. Surgeons, leave this appendix in.)

But first, the sales pitch: For me, it starts with a respectful invitation. Then it addresses the three issues bulleted above: information, attitude check(s), and then an offer.

An invitation? "There's some information about how learning meditation that I think could help improve your health. OK to discuss that?" That sounds basic, but it's just respectful ... and collaborative. It also can pick up any sense of suspicion that may need addressing, and in some cases signify a dealbreaker from any further effort in discussion.

With some agreement to proceed ...

- The information part is straightforward. Relating the benefit of, say, a relaxing of muscular tension once we open to its presence rather than ignore it, is a fruitful approach. For therapists, we can offer that in tuning into interior states of experience, we can learn how emotional tone and somatic sensation often interplay with ritual “loops” of thought. We can begin to identify what external inputs may trigger those patterns. For those in psychotherapy, this ongoing, interior observation of how one’s mind works with its patterning can generate rich material to cull for meaning.

- As for attitude piece, the practical defining of mindfulness as a capacity—a skill that can be trained up—is a useful response to concerns about some spiritual bait and switch, an attitude of distrust of the healthy goal. The other part about attitude is to frame the optimal attitude in which to learn meditation: pro-curiosity and self-compassion, anti-judgy and outcome-driven. "This works best when we just put effort into trying to observe things, not about striving for some expected way of feeling." It's about adaptation, not fixing something in the moment. Of course, reinforcing the overall benefits of feeling calmer and more adaptive to daily life difficulties, over time, on and off the cushion, are sensible.

- The "offer" part may sound weird, perhaps out of motivational interviewing tactics in recovery work. But we're contracting for some personal effort outside the care interaction; some "homework." Being direct about expectations—whether with your own teaching or via an app—sets some goals in terms of commitment and reporting back, and improves compliance.

Last thing: as a practice about an interior, subjective state, nothing can replace one’s direct experience in basic meditation in being able to teach it to our patients and students, as well as in modeling its benefits.

Having taken meditation out for a spin is all but essential in helping patients with their own "buying" decision. (No plaid sports jacket necessary.)